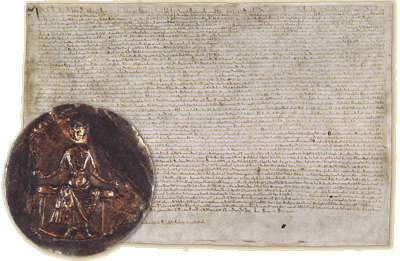

Today marks the 800th anniversary of the signing of the Magna Carta. There are articles about this everywhere, but for those who have managed to miss them, the Magna Carta was a charter originally signed (or rather, sealed) by King John, which set in stone certain fundamental rights of law, and limited the power of the King so that he was no longer above the law. This was a radical move, and in fact, the charter was signed under a certain amount of duress, nobody stood by its commitments, and it was quickly annulled by the Pope… Still, it had great symbolic as well as practical value, and after John’s death in 1216 it was rewritten several times, was part of a treaty in 1217, and in 1297 it became part of England’s statute law. It is considered to be one of the foundations of our legal system.

Disclaimer: I’ve never studied law, so do not expect great legal insights from this post. On the other hand, I did major in medieval history, so if you find history intensely boring (how can this be?), you might want to skip the next three paragraphs. I promise we’ll get to the politics/law stuff after that.

Anyway, the fun thing about the Magna Carta, at least for me, is that while most people who have heard of it think of it as being a great big document that underpins the legal system, an awful lot of it is really about 13th century politics. Most people reading this blog are not, I imagine, terribly exercised over the fate of the Welsh hostages or the Scots princesses (unless, like me, they read a lot of Sharon Penman at an impressionable age), nor do most of us care very much whether the English church – by which, of course, I mean the Catholic church in England – has free elections. I also doubt that most of us find ourselves lying awake at night worrying about scutage, or knight’s service. Moreover, while I am personally quite curious as to the nature of the ‘evil customs relating to forests and warrens’, not to mention the proper handling of ‘forest offences’, they are probably no longer in need of immediate and urgent investigation. (Hands up all those who saw ‘forest offences’ and ‘King John’ and immediately thought ‘Robin Hood’. Alas, despite the delicious coincidence, this really isn’t a Robin Hood reference in real life. It turns out you can’t believe everything you see on Dr Who…)

Then there are the clauses which, while serving a judicial rather than a political purpose, deal with matters that have become less relevant, or which reflect a very different worldview. There are, for example, several clauses in the Magna Carta about the rights and duties of guardianship of orphaned minors, which were obviously highly important in an era when death in young adulthood was common – but while a number of the principles are still in place today, they are in much less common use. For those worrying about housing affordability, I recommend to your attention Clause 25, which establishes that rents on the land should never increase. It’s almost impossible to imagine how that would affect our capitalist economic system. As a woman, it’s nice to read in this Great Charter that if widowed, I should have immediate access to my dowry and could not be forced into a second marriage, but less pleasing to learn that I don’t count as a credible witness or someone who can bring suit, except in the case of my husband’s death. I think I shall forgo my non-existent dowry for the sake of legal personhood, thank you. And, knowing how John’s elder brother Richard I felt about the Jews, I’m pleased and slightly surprised to see that debts to Jews are apparently to be treated the same way as debts to non-Jews.

While this document is far too steeped in feudal rights to be considered remotely egalitarian, I think you can discern in it the beginnings of a move towards treating people in a more equal fashion. Even if they are (and I realise that this will be shocking to some) Welsh.

I’ve just lost everyone who isn’t a history geek, haven’t I?

Anyway, in between these rather specific and sometimes outdated clauses, there are, in fact, a number of important clauses that really are central to our concept of law – and that are actually a little hair-raising if you consider that they were evidently put in place to correct things that were actually happening.

Here are some of my favourites:

(27) If a free man dies intestate, his movable goods are to be distributed by his next-of-kin and friends, under the supervision of the Church. The rights of his debtors are to be preserved.

The King can’t take your stuff if you die without a will. Nor can your local Baron.

(28) No constable or other royal official shall take corn or other movable goods from any man without immediate payment, unless the seller voluntarily offers postponement of this.

While there are provisions for taxes or their equivalents elsewhere, the King also can’t take your stuff while you are alive, without paying you. And doesn’t that paint a lovely picture of what was going on in England before this point? Incidentally, later Kings didn’t like this clause (it’s much more fun just being able to take stuff when you want it), so they introduced ‘benevolences’ which were voluntary gifts to the King from his loyal and loving subjects. I’m sure you can imagine just how voluntary they were, especially if one’s loyalty was in question. Richard III outlawed Benevolences in1484, but they were reinstated by Henry VII and continued on into the Stuart era.

Off-hand, I can think of two areas in the modern era where this sort of law is still relevant: governments requiring people to sell their land so that roads can be built, and the police confiscating items that may be evidence of a crime. And we do hear about both these things being abused on occasion – but it’s worth noting that we do, in fact, have laws on the books that limit this and protect us against truly egregious abuses, and these laws are the direct descendents of the Magna Carta’s 28th clause.

(38) In future no official shall place a man on trial upon his own unsupported statement, without producing credible witnesses to the truth of it.

(39) No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.

(40) To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.

Not even if they come here by boat and without an invitation.

There are three highly dubious measures being discussed in Parliament at present. There was Tony Abbott’s infamous proposition to give the Minister for Immigration powers to strip Australians of citizenship if they were thought to be terrorist sympathisers, without necessarily being convicted of anything by the courts. This has now been ruled out for those who are Australian-born and Australian-only citizens, but is still being contemplated for those with dual citizenship. You can read (and respond to) the discussion paper here. This a dangerous bill for three reasons. First, it appears to punish people for thoughts and intentions rather than for actions. Second, it bypasses the legal system, undermining any notion of ‘innocent until proven guilty’. And thirdly, the perception is that this will largely target Muslims and people of Middle Eastern descent. Will it do so? Possibly. But whether it does or not, that’s certainly how it is being viewed in Australia’s Muslim community, and this only makes life harder for those Muslims who are trying to be good Australian citizens.

Then we have the bill that would give guards in Detention Centres powers to respond with “reasonable force” not just to protect life or property in a Detention Centre, but also to “maintain the good order, peace or security of an immigration detention facility”. This is disturbing on several levels. For one thing, nowhere does the Bill attempt to define reasonable force (bizarrely, the only thing the bill seems to rule out is force-feeding – but it does not rule out deadly force); for another, the part about maintaining good order and peace sounds like a licence to use force to quash peaceful protests. And there is very little recourse for those who have had ‘reasonable force’ used against them – no ability to challenge this in court, just the possibility of making a complaint to the Secretary of the Department of Immigration and Border Protection, and “The investigation is to be conducted in any way the Secretary thinks appropriate.” (Clause 197BC). This does not sound very reassuring. You can read the full legislation here. Unfortunately, it is too late to make a submission to the Senate, but it is not too late to contact your local senator. In particular, the cross-bench senators Ricky Muir, Bob Day, John Madigan and David Leyonhjelm would be good choices to contact.

Finally, there is the Australian Border Force Bill 2015, passed, I regret to say, by both the Coalition and the ALP, which increases the secrecy requirements for those working in or visiting detention centres. Essentially, one may not report anything that one witnesses in a detention centre to anyone outside the Department of Immigration. Doing so carries a jail term of up to two years. Once again, this effectively means that all policing of detention centres is internal – there is no external body, legal or otherwise, to which one can turn if reports of abuse are ignored or rejected.

Look, I’m not saying that people working for the Department of Immigration are evil. I suspect most of them are doing the best they can, under increasingly unpleasant conditions. A person doesn’t have to be evil to be misinformed, or weak, or consciously or unconsciously biased. Hell, a person doesn’t have to be evil to be overwhelmed by their workload and unable to investigate allegations in a timely or thorough manner. This is not about assuming bad faith on the part of people working within this system.

What I’m saying is that nobody, no matter how well-intentioned they are, should be in a position where they have life or death power over others, with no oversight and no recourse. Because the best-intentioned, kindest, most compassionate, fairest person in the world can still make a mistake, and the stakes here are really high. And we already know we have a problem. We know that people working in prison systems have difficulty resisting the pull to dehumanise prisoners. We know that there have been multiple allegations of abuse of women and children within our detention centres, that even if every single allegation is false, that our detention centres have been found to be inherently damaging environments for children. We know that at least two people have died in our detention centres who would not have died if they had not been there. And I think everyone is now aware of the findings of the Australian Human Rights Commission on this subject. It’s gruelling reading.

The solution to this situation is not more secrecy. It’s more oversight. And, ideally, more compassion.

800 years ago today, a bunch of warring and self-serving barons who were not known for their kind hearts or noble natures had already figured out that it was really important to limit the power placed in the hands of any one person. They had seen exactly what could happen when such power was abused, and were willing to place some limits even on their own power if it meant limiting the power of the King, or of any single person, to be judge, jury and executioner. They recognised that absolute power without any controls on it was supremely dangerous to everyone’s liberty. Surely, 800 years later, we are intelligent enough to recognise the same thing?

The barons were willing to fight to change their situation – even to the point of threatening to depose a reigning King, an act which could condemn them to a slow and painful death for treason. (And as if that wasn’t bad enough, treason was at that time also considered a crime against God, which would condemn one to eternal damnation.) For most people reading this, the stakes are not so high. It’s not everyday Australians who will suffer if these laws get passed, it’s the ones who came here as refugees or as immigrants hoping to start a new life in a country where they could live and work in peace. It’s the ones who are a religious minority. The ones whose parents were born in a country that we don’t like very much just now. The ones who are a little bit different to the rest of us.

Even if we are selfish enough not to care about this, we should perhaps consider that the people who will be affected by these laws – the people whose rights are already a little bit less than ours – are the canaries in the coalmine. There’s still enough oxygen for the rest of us, but how long will it last?

These laws, if passed, will set a very dangerous precedent, and one that could affect us all in the long run.Here’s the final clause of the Magna Carta:

Well said; brava!

“…nobody, no matter how well-intentioned they are, should be in a position where they have life or death power over others, with no oversight and no recourse. Because the best-intentioned, kindest, most compassionate, fairest person in the world can still make a mistake, and the stakes here are really high.”

Yes! Exactly this ^^

(Another history geek, here 🙂 )

Hooray for history geeks!